The Hankyu Railway is one of Osaka, Japan’s “Big Four” private railways. It operates three routes out of its Umeda Terminal in central Osaka: the Kobe, Takarazuka, and Kyoto lines. It does so with extremely high throughput, operating roughly twelve trains an hour all day, every day on its Kobe and Takarazuka lines. (It operates trains on the Kyoto Line with even greater frequency.) This is a frequency and reliability that continues to elude American mass transit agencies. This raises the question: how does Hankyu do it?

The answer is that Hankyu does not run complex schedules with very many stopping patterns. Instead, they operate very simple schedules in very short intervals. This creates “pulses” of movement throughout the system, a rhythm so regular you can set your watch by it. This idea of a simple, regular, and highly rhythmic schedule is known as takt in English, a term coined by Anglophone transit planners from their German cousins. Building schedules to takt maximizes throughput on space-constrained mainlines.

Hankyu and Takt

The most regular schedules in the world are the ones achieved by single line subways, such as the ones in the Paris Métro. This is not a coincidence. These systems are closed, their equipment’s performance characteristics are well known, and operations planners can schedule throughput with extremely short intervals. Some of the world’s busiest subway lines achieve intervals as low as 90 seconds on two track infrastructure.

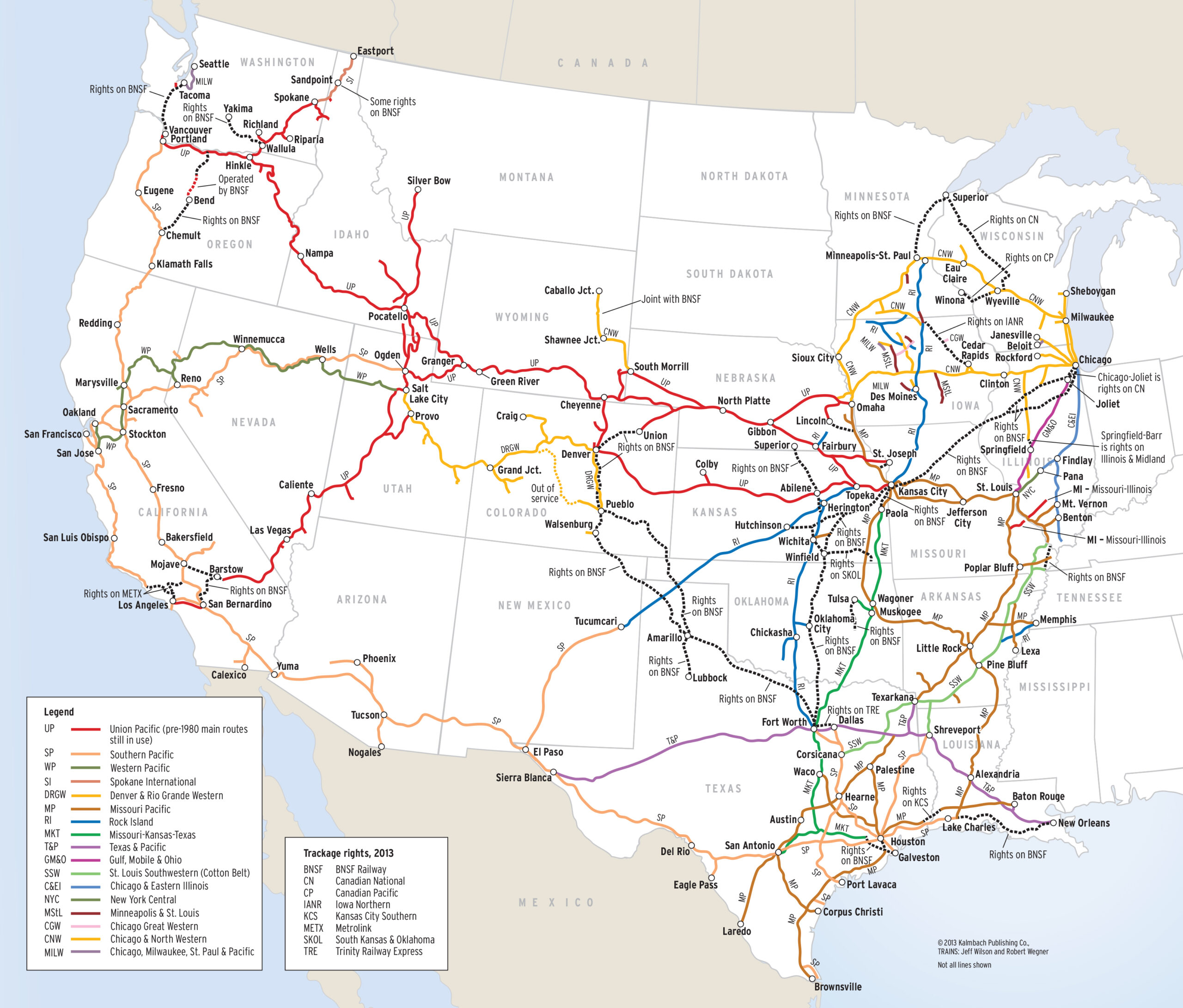

The situation is a bit different for Hankyu. First, none of its lines are closed. The Kobe Line interlines with the Hanshin and Sanyo railways through central Kobe; the Takarazuka Line connects with the Nose Railway, which operates some through service to Osaka via Hankyu; and the Kyoto Line’s branch to Senri through-runs with the Osaka Metro’s Sakaisuji Line. Secondly, the Hankyu network is highly branched. The Kobe Line has branches from the mainline to Itami, Imazu, Takarazuka, and Koyoen; the Takarazuka Line, besides the bespoke Nose Railway (which itself branches twice), has a branch to Mino’o; and the Kyoto Line, besides the branch to Senri, also has a branch to Arashiyama. Finally, Hankyu’s ridership is more “interurban” than “intraurban”; that is, its riders expect fast service between distinct cities moreso than they expect stops at various points of interest within the métropole. While inarguably efficient, running all-stops trains at constant intervals is suboptimal in terms of ridership expectations. Simply put, Hankyu’s riders do not expect to stop between e.g. Osaka and Kyoto.

The solution to this problem is to operate multiple, highly regular, service profiles on the line. That is, there is a strong distinction between “local” and “express” trains, where local trains stop at all stops along the line while express trains only stop at a set subset (as it were) of these stops; namely, the busiest. Thus, while the Kobe Line has approximately 20 stops from Hankyu’s Umeda Terminal to Shinkaichi, express Kobe trains only stop at a third of these, mostly concentrated in the Nishinomiya and Kobe areas. Because express trains are faster than locals, they set the interval rhythm. That is, they set the takt. Express trains leave Umeda at :X0 (ten, twenty, thirty past the hour, and so on); local trains leave once the express has cleared the block, allowing a clear signal — approximately a minute later.

During the day, Kobe Line trains run in ten-minute intervals. This means that a local-express pair departs Umeda once every ten minutes. The same is true of Kobe’s main station, Sannomiya. Hankyu goes a step further, too: it uses the takt it established on the Kobe Line to schedule the Takarazuka Line. In fact, Kobe Line and Takarazuka Line trains depart regularly on the same intervals! However, Hankyu does not extend this Kobe-Takarazuka takt to the Kyoto Line. This is because the Kyoto Line has the longest run of the three, and has three primary service patterns (instead of the two the other two lines share). Because of this, the Kyoto Line has a different natural interval than the other two, one which sees three departures in 12 minutes rather than two in 10. (That is, the Kyoto Line’s midday frequency is ~18 trains per hour (tph).)

Takt-Supporting Infrastructure

The idea of the takt is that Kobe Line express trains are faster than its local trains. Moreover, Kobe Line express trains are more than nine minutes faster than its local trains! What this means is that either (a) line capacity is set by the minimum interval in which the line stays clear (about 20 minutes), or (b) infrastructural investment must be made to support the takt. This is the concept of a timed overtake. Simply put: at some point between Osaka and Kobe, the express train runs into the preceding local train. The point where this occurs can, of course, be calculated, given average train speeds. Thus, the station closest to (but not beyond) the collision point needs to be a passing siding as well as a station. This is where faster expresses are able to pass slower locals. On the Kobe Line, this occurs at Nishinomiya-Kitaguchi.

Stops at Nishinomiya-Kitaguchi have this rhythm: First, a local train pulls into the station. Roughly a minute later, they are followed by an express train. This meet facilitates a cross-platform transfer, which is useful for passengers wishing to go beyond Nishinomiya but not quite all the way to downtown Kobe (or Osaka, in the other direction). The express train departs. Finally, once the block clears, the local train departs as well. It should be apparent that this process ensures that the dwell time for locals at the meet point is quite long — at least three minutes and perhaps as much as five. In fact, this dwell time is so long that locals may be thought of acting as different routes altogether on either side of the timed overtake. However, without this timed overtake, it is impossible to achieve the frequency Hankyu achieves on what is fundamentally a two-track mainline.

The Takarazuka Line is significantly shorter than the Kobe Line. Unlike on the Kobe Line, where expresses pass locals at Nishinomiya-Kitaguchi, on the Takarazuka Line, locals terminate where following express trains meet them. This occurs at Hibarigaoka-Hanayashiki. What this means is that Takarazuka Line trains have two distinct service patterns: (1) express trains which originate at Takarazuka, and (2) local trains which originate at Hibarigaoka-Hanayashiki, and depart that station once expresses clear the block ahead. For both the Kobe and Takarazuka lines, Hankyu’s operations planners identified where the timed overtake was to occur given a specific all-day service profile, and designed the infrastructure to fit that profile.

This targeted investment can also be used to allow for even tighter intervals. On the Kobe Line, Sonoda station — approximately halfway between Umeda and Nishinomiya-Kitaguchi — is a fully four-track station, despite only seeing local service. The same is true for Sone station on tbe Takarazuka Line (approximately halfway between Umeda and Hibarigaoka-Hanayashiki). Unlike these two, however, passing tracks run through the middle of Rokko station (approximately halfway between Nishinomiya-Kitaguchi and Kobe-Sannomiya). In all three of these cases, however, the added infrastructure allows for timed overtakes at double the line’s normal frequency. The Kobe and Takarazuka lines are therefore able to handle frequencies of up to 24 tph. This helps Hankyu both manage peak loads, and provide peak service paradigms outside of its two (or, in the Kyoto Line’s case, three) normal service paradigms.

There is one other point to make about Hankyu’s physical plant here. Each of the three lines heading to Umeda has its own separate two-track mainline, each leading to three bay platforms. Three tracks, as it turns out, is more than adequate for Hankyu’s short-turn traffic, and three-track terminals is standard practice among railroad lines throughout Japan: Hankyu and Hanshin’s original termini at Sannomiya likewise had three tracks, as do Hankyu’s Kyoto terminus at Kawaramachi, Kintetsu’s original Nara Line terminus at Namba, Kintetsu’s terminus at Nara, the Kobe Electric Railway’s terminus at Shinkaichi, JR’s Nara Line and San’in Main Line termini at Kyoto, and Kintetsu’s Kyoto Line terminus at Kyoto, among others. Because the Kobe, Kyoto, and Takarazuka lines all depart onto their own segregated mainlines rather than to a unified trunk, there is no need for Hankyu to build a massive throat linking all nine tracks at Umeda. It also allows Kobe and Takarazuka line trains to have simultaneous departures, and Kyoto Line trains to have near-simultaneous departures (which can become simultaneous when their respective takts line up).

In other words, capital investments on the Hankyu system are guided first and foremost by a primary service profile — what is necessary to support a takt that best balances competing ridership demands with a minimum of schedule variations. This allows Hankyu to achieve 12 tph frequencies on the Kobe and Takarazuka lines all day, every day, and 15 tph frequencies on the Kyoto Line all day, every day. This is in direct contrast to the United States, where capital investments tend to occur as a hedge against poor operations planning, which in turn results in excessive capacity that enables even poorer operations planning. However, Hankyu’s three mainlines do not exist in a vacuum. They are fed by a feeder network of at least a dozen branches and two feeder railroads, and themselves interline with four other railroads (including one of the feeder routes).

But What About Branching?

One may have noticed already that the Hankyu network is heavily branched. It has around half a dozen branches, and in addition to this, it has a feeder route (the Nose Railway) which acts as a branch in its own right; a second feeder route with a free transfer (the Kobe Electric Railway); and interlines with three more routes (the Osaka Metro, the Hanshin Electric Railway, and the Sanyo Electric Railway).

In European, Australian, and North American systems, not only are suburban rail lines quite heavily branched, but the rider expectation is that the train they board will take them directly into the city center. This is likely closely related with the low-frequency clockface schedules one finds in outer-suburban regions, if such schedules meaningfully exist at all. Furthermore, as Alon Levy notes, transfers incur a ridership penalty; they are necessarily inconvenient, and the longer the transfer, the less convenient it is, and the greater the penalty.

By contrast, Hankyu follows Jarrett Walker’s “Frequency is Freedom” dictum. That is, Hankyu does not directly route trains from any of its branchlines to Umeda. Instead, its branchlines are serviced by their own, independent shuttle train operations running from the branch terminus to the mainline junction. Like the mainline, these branchline trains also have high frequencies. In fact, their frequencies are so high (the Koyo Line has a frequency of 10 minutes; the Imazu Line to Takarazuka of 7.5 minutes; the Imazu Line to Imazu (these operate independently) of 10 minutes; the Itami Line of roughly 7.75 minutes; the Mino’o Line of 10 minutes; the Nose Electric Railway (ignoring its own branch) of 10 minutes; the Senri Line of about 6 minutes; and the Arashiyama Line of about 8 minutes. These, note, are all-day frequencies; I checked the schedule at half past eight in the evening. By implementing high-frequency service both on mainline and branchline alike, Hankyu is able to minimize the transfer penalty at its junction stations.

This is not to say the transfer penalty does not exist, however; Hankyu’s branchlines’ ridership is noticeably lower than its mainlines’, and it is fairly evident that its profitable mainline services cross-subsidize far less profitable branchline services.

Of note here, while Hankyu’s practices regarding their branchlines are standard among the private operators, the largest operator in the area, JR West, follows a different practice on their Urban Network. The Urban Network is massively interlined, facilitating anywhere-anywhere service patterns (within limits). It operates more in line with European norms than do Hankyu, Hanshin, Sanyo, Keihan, Kintetsu, Nankai, or any of the other minor operators within the region. Thus, trains on the JR Kobe and Takarazuka lines, which converge at Amagasaki, may run either towards Kyoto and beyond via Osaka Station or towards Kizu (and Nara and beyond) on the Gakkentoshi Line. Trains on the JR Hanwa Line (Osaka – Wakayama), Kansai Airport Line, and Yamatoji Line (Osaka – Nara) may terminate at Osaka (Tennoji for the Hanwa and Kansai Airport lines; Namba for the Yamatoji Line), or they may continue to JR-Osaka via the Osaka Loop Line. JR West supports this extensive interlining with a quad-track mainline from Maibara in the east, through Kyoto, Osaka, and Kobe to Nishi-Akashi in the west, as well as with double-tracked mainlines everywhere else.

Like the private railways, JR supports extensive clockface scheduling and takt operations across its system. However, because it uses operating practices more akin to Western regional rail rather than the metro network-style practices Japan’s private operators favor, it necessarily has more complex operations which in turn lead to reduced services across some of its lines, e.g. infrequently spaced (by Japanese standards) locals on the Hanwa Line. Its operational practice of through-running Wakayama and Kansai Airport expresses to JR-Osaka is also a significant driver of congestion on the Loop Line, Osaka’s answer to Tokyo’s famous Yamanote Line; in order to alleviate this, JR is intending to build a regional-rail-style central tunnel along Naniwasuji through the western side of central Osaka. This will pair with the Tozai Line, a tunnel linking the Gakkentoshi Line on Osaka’s east side with the Kobe and Takarazuka lines on its west side; ideally, the Naniwasuji tunnel will also allow JR to design a more operationally coherent network.

We have thus so far found that Hankyu’s operations practices are built around a very simple schedule, repeating at a regular rhythm. This we call takt. Having implemented this type of schedule, Hankyu then uses it to inform its capital investment strategy. It creates larger stations, either quad-tracked or with passing sidings, where express trains can meet locals (for cross-platform transfers) or overtake dwelling locals. Specifically, Hankyu has built facilities for timed overtakes at Rokko, Nishinomiya-Kitaguchi, and Sonoda on the Kobe Line, and at Hibarigaoka-Hanayashiki Sone on the Takarazuka Line; these facilities support peak frequencies of 24 tph and all-day frequencies of 12 tph, or two trains, one express and one local, per 10-minute interval. (They have also presumably built similar facilities on the Kyoto Line, but we have not taken the time to analyze this.) In addition, they have also constructed a six-track trunk leading out of Umeda, organized into three separate two-track lines, in order to support simultaneous departures.

However, there is one more significant consideration we need to give to Hankyu’s scheduling practices, and that is how the Kobe Line interlines with the Hanshin and Sanyo electric railways in central Kobe.

Hankyu and Interlining

Hanshin and Sanyo

In 1968, the Kobe Rapid Railway opened. This underground railroad linked the Sannomiya termini operated by the Hankyu and Hanshin electric railways, respectively, with the Sanyo Electric Railway on the other side of Kobe. It also extended the Kobe Electric Railway, a minor operator in the city’s mountainous north side, to a new terminal at Shinkaichi, one with a free transfer within the farezone. With the Kobe Rapid Railway, Hanshin and Sanyo began extensive through-running; even to this day, the Hanshin and Sanyo networks remain operationally unified.

The Hanshin-Sanyo mainline has even more complex operations than the Hankyu Kobe Line. (Like Hankyu, Hanshin operates trains from a terminal at Umeda in Osaka.) There are no fewer than five basic operations Hanshin and Sanyo run along their combined line:

- Express trains from Umeda to Himeji (these are the true Hanshin-Sanyo shared expresses)

- Express trains from Umeda to Higashi-Suma, just past the Kobe Rapid Railway’s western portal (these are the Hanshin expresses)

- Express trains from Himeji to Hanshin-Sannomiya (these are the Sanyo expresses)

- Local trains from Hanshin-Umeda to Kosoku-Kobe, a station within the Kobe Rapid Railway tunnel

- Local trains from Himeji to somewhere in Kobe (Sanyo allows Shinkaichi and both the Hankyu and Hanshin Sannomiya termini as potential endpoints).

Above and beyond this, Hanshin also fits trains running from Sannomiya to Amagasaki (where the Namba Line diverges from the Hanshin mainline) and on to Namba on Osaka’s south side and Nara via the Kintetsu Railway in their operations pattern. Like Hankyu, both Hanshin and Sanyo build their schedules around 10-minute takts; this is true even though the Hanshin line between Osaka and Kobe has nearly twice as many stops as either JR or Hankyu.

Like Hankyu, Hanshin and Sanyo both make extensive use of timed overtakes to yield both a frequent all-day takt and the ability to schedule the takt at double frequency (or run non-takt variants) during peak hours. Heading east from Sannomiya, timed overtakes are available on Hanshin at Oishi, Mikage, Ogi, Nishinomiya, Koshien, Amagasaki-Center-Pool-Mae, Amagasaki, Chibune, and Noda. Of these, I can only say with certainty that Mikage and Nishinomiya are used for timed overtakes during normal frequencies, although the pattern strongly suggests Pool-Mae and Chibune are as well.

Heading west from Shinkaichi, timed overtakes are available on Sanyo at Higashi-Suma, Sanyo-Suma, Kasumigaoka, Sanyo-Akashi, Fujie (on the eastbound side only), Higashi-Futami, Takasago, and Oshio. Keeping in mind the every-other-overtake rule and the fact that Fujie clearly cannot be used for westbound timed overtakes (and therefore can only be used for peak-hour times heading eastbound), the timed overtakes Sanyo uses to maintain normal frequency are (1) Sanyo-Suma, (2) Sanyo-Akashi, (3) Higashi-Futami, and (4) Oshio. Strangely, it does not appear there is a timed overtake between Oshio and Himeji (Shikama’s center track is a stub track for Sanyo’s Aboshi Line), which is perhaps mitigated by Himeji itself being a four-track terminal.

This allows both the Hanshin and Sanyo mainlines to employ the same takt schedule that Hankyu employs on its Kobe and Takarazuka lines. This is especially beneficial for Hankyu because it can time its Kobe Line departures from Shinkaichi to fit within Hanshin-Sanyo’s takt. In addition to this, Hanshin can program its Nara trains (departing from Sannomiya) to fit into available slots left over in its takt.

Finally, it is worth noting that Hanshin times its locals to terminate at Kosoku-Kobe with a cross-platform transfer to Hankyu, and Sanyo times its locals to depart Shinkaichi, the next station up, a minute after Hankyu arrives. This complex double cross platform transfer is the product of a well defined takt combined with the strict operational discipline needed to maintain it.

Nose and Kobe Electric Railways

However, any discussion of interline movements in the Hankyu system is incomplete without a discussion of such movements in Hankyu’s feeder railways. There are, recall, two: (1) the Kobe Electric Railway and (2) the Nose Electric Railway. These two feeder systems handle interlined operations in very different ways.

The Nose Electric Railway connects to the Hankyu Takarazuka Line at Kawanishi-Noseguchi and its mainline runs from there north to Yamashita. At Yamashita, two branches diverge. One runs west to Nissei-Chuo; the other runs east to Myokenguchi. Despite the apparearance of a complex system, Nose is actually operationally simple. It runs three services: one from Kawanishi-Noseguchi to Yamashita, one from Yamashita to Nissei-Chuo, and finally one from Yamashita to Myokenguchi. Because it runs these three services separately, it is able to provide 10-minute frequencies on all three, rather than having either (a) a mainline with double the frequency of the branches or (b) a branch that has a significant frequency penalty relative to the mainline.

By contrast, the Kobe Electric Railway is what the FRA would call a “sealed system”. Unlike the Nose Electric Railway, which is connected to Hankyu’s Takarazuka Line at Kawanishi-Noseguchi, the Kobe Electric Railway has neither the track gauge nor the structure gauge of Hankyu. It runs on narrow-gauge tracks, like JR and unlike the rest of the Hankyu network (excepting the Osaka Monorail), which uses standard gauge, but it uses a narrower structure gauge than JR. There are no track connections between the Kobe Electric Railway and any other railway, anywhere.

Unlike anything else in the Hankyu system, the Kobe Electric Railway practices extensive interlining of its two mainlines, the Sanda Line linking Shinkaichi with Sanda and the Ao Line linking Shinkaichi with Ao. During the day, the Kobe Electric Railway runs trains along the Sanda Line once every ten minutes, and it also runs a shuttle along the Ao Line from Nishi-Suzurandai to its junction with the Sanda Line at Suzurandai at roughly the same interval. (It should also be noted that this stretch of the Ao Line is single-tracked, so this shuttle runs at the maximum available interval.) It also runs trains from Shinkaichi to Shijimi, Shinkaichi to Ono, and Shinkaichi to Ao at significantly lower frequencies than the shuttle train between Suzurandai and Nishi-Suzurandai. Communities along the Ao Line west of Nishi-Suzurandai have service frequencies under 20 minutes outside of peak hours; they are noticeably underserved relative to the Kobe Electric Railway mainline to Sanda, or anywhere on the standard-gauge Hankyu network.

Lessons from Japanese Operations

Lesson 1. Schedules need to be simple and rhythmic.

It is quite common for American commuter rail schedules to have extremely complex service profiles. This is particularly bad on LIRR’s Port Jefferson Branch, which appears to have as many distinct service profiles as weekday trains serving the line, and there are a lot. (I wish I was kidding.) However, takt scheduling demands the opposite approach. It demands a high degree of regularity to departures, and stemming from that, a scheduling approach that minimizes variations in schedule profiles. In fact, Japanese railways post all possible stopping patterns a line can have, if it has more than one (and most do), over at least one car door in every train car. The space constraint such posters create further limits the temptation for Japanese operators to create unnecessarily complex schedules.

Simple schedules are also repeatable schedules. This means that the schedule should be optimized to a given interval of repetition, preferably a divisor of 60 (so that the schedule can repeat at minimum once an hour) or of 30 (so that the schedule can repeat at minimum once every half hour). As we have seen, Hankyu’s systemwide schedules repeat on frequencies of 10 or 12 minutes, if not even more frequently. This makes takts extremely easy: a 10-minute schedule repeats 6 times an hour, and a 12-minute one, 5 times. Also notice here that the takt’s basic pulse need not be a singular departure: Hankyu’s basic pulse sees two departures every 10 minutes on the Kobe and Takarazuka lines, and three departures every 12 minutes on the Kyoto Line. This means that the all-day hourly frequency is 12 trains an hour on the Kobe and Takarazuka lines, and 15 trains an hour on the Kyoto Line.

Lesson 2. The schedule should identify chokepoints, where capital improvements can then be concentrated.

Optimally, a railway line should run a single service frequency, namely, all-stops locals at the greatest frequency the signaling system allows. This is how subways operate. However, passenger demands often create mixed service profiles. This means that an operator might need to run express trains (which skip stops) along the same line as local trains (which do not). Sooner or later, the express train is going to run into the preceding local.

If Hankyu’s Kobe Line were two tracks the entire length, it would be horrendously inflexible in terms of schedule profiles. Either it could run locals at extremely high frequencies, local-express pairs at a 20-minute interval (it takes 20 minutes for an express to catch up to the previous local at Sannomiya), or semi-expresses with ad-hoc stop skippage in order to try to balance service loads from various stations (which is why the Port Jefferson Branch’s schedule looks like drunk stoners on cocaine planned it). Instead, by building the Kobe Line’s primary operations profile around 10-minute frequencies, Hankyu was able to identify the capital investment necessary to achieve such frequencies. This turned out to be quad-tracking the its midpoint station, Nishinomiya-Kitaguchi.

Quad-tracking a single station is obviously a lot cheaper than quad-tracking the entire line. But the limited capital expense was optimally placed to maximize operational leverage. By placing the Kobe Line’s quad-track station where expresses catch up with locals when departures have 10-minute intervals, it doubled the line’s frequency, given the mixed service profile, from 6 tph to 12. Essentially, the quad-track station at Nishinomiya-Kitaguchi allows Hankyu to have both frequent fast trains and frequent trains that stop everywhere on the same two-track Kobe Line.

Hankyu pushed this concept further: they quad-tracked two other stations on the Kobe Line, Rokko and Sonoda. Each of these stations lie at the midpoint between Kobe-Sannomiya and Nishinomiya-Kitaguchi and Nishinomiya-Kitaguchi and Osaka-Umeda, respectively, which allows Hankyu to schedule 2 departures every 5 minutes, or a 24 tph base schedule, at peak frequencies using the basic unit of departure. They can achieve greater throughput still during peak hours by building schedules with somewhat different local and express patterns, such as locals which terminate at Nishinomiya-Kitaguchi and trains which express to Nishinomiya-Kitaguchi and run local past it. It also implies that the Hankyu Kyoto Line has a peak frequency of at least 30 tph, barring fouling issues the Senri Line creates at Awaji.

Lesson 3. Timed overtakes are your friend.

Mixed-traffic is both ubiquitous and difficult. Unlike in an environment where every train is expected to make every stop with high frequency, it is impossible to maintain consistent spacing in mixed-traffic schedules. As an express train moves along the line, it gets further away from the local train behind it and closer to the one in front of it. American schedules tend to mitigate this by making most trains not-quite-expresses and not-quite-locals. This results in every stop getting similar (irregular) service. However, this solution is highly suboptimal.

As Hankyu’s Kobe Line shows, timed overtakes unlock capacity along a given route. Without timed overtakes, the Kobe Line would have to be (a) operated either like a subway line with very high throughput capacity but a stopping pattern that would render the longest Hankyu runs uncompetitive against JR, (b) with express speeds that would allow the longest runs to be competitive against JR, but with frequencies that limit the effectiveness of this competition, or (c) with a schedule that made every train stop at some, but not all, local stops (which would render Hankyu uncompetitive against JR both in terms of frequency and speed).

By building a passing facility at Nishinomiya, Hankyu unlocked frequency. Their available throughput went from 2 departures every 20 minutes (6 tph) to 2 departures every 10 minutes (12 tph). With that passing facility, it was able to run trains fast enough to match JR’s time from Osaka to Kobe, at frequent enough intervals to match what JR could achieve on their quad tracked mainline. They were further able to unlock frequency by adding passing facilities at Rokko and Sonoda, allowing peak frequencies of 2 departures every 5 minutes (24 tph). In other words, through the magic of timed overtakes, Hankyu was able to make their two-track line mimic a four track line’s frequency.

This is an especially important observation when one considers that a great deal of American light rail infrastructure (hello DART!) runs on two-track lines that extend far out into the suburbs. By building a schedule such that expresses will always overtake locals at predefined locations, and providing infrastructure capable of handling the meet, an operator like DART can achieve throughput, and hence frequency, that mimics what a four-track mainline is capable of even without having a four-track line in its own right.

Lesson 4. Branching is a double-edged sword.

Modern American network design tends to heavily emphasize interlining, and most European commuter-rail variants heavily branch. The same is true of the Japanese rail network. However, the way Americans, Europeans, and Japanese handle branching is very different.

In Euro-American contexts, branching is viewed as a way to achieve greater trunkline frequencies. If all trains are scheduled to access the city center, then the trunkline frequency can be stated as the sum of branchline frequencies. However, this approach has consequences. It privileges frequencies on the trunk over those on the branches. For example, a trunk with two equal branches can achieve a frequency of one train every 10 minutes only if the branches are allowed to have frequencies of one train every 20 minutes. High frequency in the core is the consequence of suboptimal frequency on the branches.

Another problem branching incurs is that it builds uncertainty into the system, uncertainty corrected for by building excess capacity. This is because the more lines feed into the trunkline, the more likely it is that a problem on one of them cascades across the system. This is a problem JR has to a much greater degree than any of Japan’s private railways. (Delays of up to 10 minutes on trains in JR West’s Urban Network, which uses Europ-American branching, are uncommon but not unheard of.)

Japan’s private railways’ solution, with exceptions, has been to separate branchline schedules from mainline ones. This allows each line to be independently scheduled, such that each service has a high degree of frequency. The flip side of this coin, however, is that branches always require transfers. These transfers can be, but are not always, cross-platform transfers. When they are not, however, one never leaves the fare area. The net result of this is that most branches on Japanese private railways operate like short shuttles linking the branch terminus with the mainline, like the New York subway’s S trains. These shuttles normally operate at 10-minute frequencies. Extremely high-frequency operations such as these minimize the impact of transfer penalties.

Perhaps the ultimate example of how much high frequencies reduce transfer penalties is the Kobe Electric Railway. The Kobe Electric Railway terminates in Shinkaichi, on Kobe’s west side and some 40 minutes away from Sannomiya on foot. However, because both the Kobe Electric Railway and the Hankyu-Hanshin-Sanyo system operate out of Shinkaichi at very high frequencies, the transfer penalty for passengers from the Kobe Electric Railway heading downtown (or towards Osaka, Kyoto, or Himeji) becomes all but invisible. The overall effect is similar to if passengers transferring at Secaucus Junction could expect their train to arrive presently without even consulting a timetable.

It should be noted, however, that part of why this solution works is because of the Kansai region’s high overall density. Around 20 million people live within a 40-mile radius of Osaka’s city hall. No US conurbation is this dense. It is a neverending sea of urbanity. However, this does not mean Japanese lessons are inapplicable. Indeed, Japanese branching habits occur not just near central Osaka, but also in its suburban and even exurban fringes. A good example of this is the Keihan Railway’s Katano Line. This route runs along the eastern edge of Osaka’s built-up area. It is far more suburban than anything closer to the core. However, Keihan Railway operates the Katano Line the same way Hankyu operates the Imazu Line, that is, as a shuttle service from its junction with the mainline to its ultimate terminus.

Thus, while branches are able to service very many more destinations than a single mainline, it is useful to question how we should go about operating them. When it comes to branches, there is a very real tradeoff to be had between high all-day frequency, on one hand, and one-seat service, on the other hand. While one-seat service may still be desirable during the peaks, frequencies that make cross-platform transfers at the junction as painless as possible are a far more optimal solution for very frequent all-day service.

Conclusion

The Hankyu Railway is one of Osaka’s largest private railway operators. It has a long history of operating intensive passenger service at a profit. It does so by operating high-capacity, high-frequency, and high-throughput service — on double-track mainlines. In order to do so, it has focused on optimizing operations and then directing capital to augment and expand operational capacity.

This is the heart and soul of the Swiss transit maxim organization before electronics before concrete. By bringing throughputs on mixed-traffic, two-track mainlines to their absolute maximum, Hankyu is able to provide world-class urban rail service at a fraction of the capital cost embedded in peers and competitors with four-track trunklines.